The Shirt is Sacred

The shirt. There is nothing more coveted. There is nothing more loved. There is nothing more hated. There is nothing more anticipated. The AJC Peachtree Road Race finisher’s shirt is annually the most discussed, debated and celebrated tradition of the world’s largest 10K.

And like almost everything else, how it was born and evolved is the stuff of Peachtree legend. Finisher’s shirts weren’t a thing when the Peachtree started because road races weren’t a thing. “It happened by accident, but we honored the accident,” said Julia Emmons, executive director of Atlanta Track Club from 1985 to 2006.

Keeping the T-shirt design a secret started out as an accident, too – there was simply no reason to take them out of the containers in which they arrived until race day, hence few eyes were laid on them before that morning. But it felt like a secret, and as curiosity and anticipation built up over the years the Club began to embrace – and intensely guard – the tradition of not revealing the design until the first Peachtree finisher crosses the line.

The design hasn’t always been selected by a contest – until 1995, the Club and the AJC designed the shirts – and they haven’t always been given to every finisher. Until the late 1970s, shirts were awarded until they ran out, giving the advantage to the fleet of foot. In fact, the only commonality between today’s finisher’s shirt and the original is its importance to the recipient.

“The shirt is sacred,” said Emmons.

In Atlanta Track Club’s archives, you’ll find hundreds of photos of people wearing their shirts in locations around the globe. You’ll find photos of quilts made from decades of collected shirts. On the walls of the Club’s office, you’ll find framed copies of each shirt signed by the elite athletes who competed in that year’s race.

And in “25 Years of the Peachtree Road Race,” you’ll find what may be the ultimate anecdote. According to author Karen Rosen, Jack Pearce was wearing his shirt the day he was hit by a van on a run. He spent eight days in the hospital. After he was released, Pearce and his wife went back to the scene of the accident and dug through the weeds and the mud to retrieve the shirt paramedics had cut off him.

None of the Original 110 at the 1970 Peachtree got a shirt. There wasn’t one. Race founder Tim Singleton got the idea after he ran the Boston Marathon in 1971 and saw shirts for sale. So, in Year Two, the first 250 finishers received a shirt. Emmons was among the 80 finishers who didn’t get one. For the duration of the 1970s, the faster you were the better shot you had a shirt. In fact, when the field size swelled to 6,500 in 1977, more than half the entrants went home empty-handed.

In the later part of the race’s inaugural decade, race organizers implemented a T-shirt clock. Shirts were available only to those who crossed the finish line in under 55 minutes.

The clock remains in place today, starting when the final runner crosses the line. But Emmons made the decision to give every registered runner a shirt when she took over the race, making the clock largely ceremonial.

What she couldn’t guarantee was that runners would get the right size. Predicting how many small, medium, large and beyond to order was a complicated science and Emmons said it took her 10 years to get it right. When she finally did, she erred on the side of ordering more larger sizes rather than smaller.

“I didn’t mind people like me being mad,” said Emmons, who stands 5’2” and weighs 97 pounds. “They don’t make a lot of noise.”

From 1985 to 1994, Emmons and her small staff at Atlanta Track Club worked with the marketing department at the AJC to create the design that would appear on the shirt. By that time, the design and color were closely guarded secrets, revealed on race day to predictably mixed reviews and met by strong feelings.

Sometimes, the feelings were largely shared. People loathed a sponsor logo on the back of the 1984 shirt (nothing ever appeared on the back of the shirt again.) The 1987 peach-colored shirt was a runaway hit.

Other years … well, everybody’s entitled to their opinion. Reacting to the 1990 shirt, one man wrote the AJC: “The Peachtree Road Race T-shirt stinks. Last year’s was awful, but this year’s was even worse.” A woman wrote of the same shirt: “The shirts of this year are beautiful and I am proud to wear mine.”

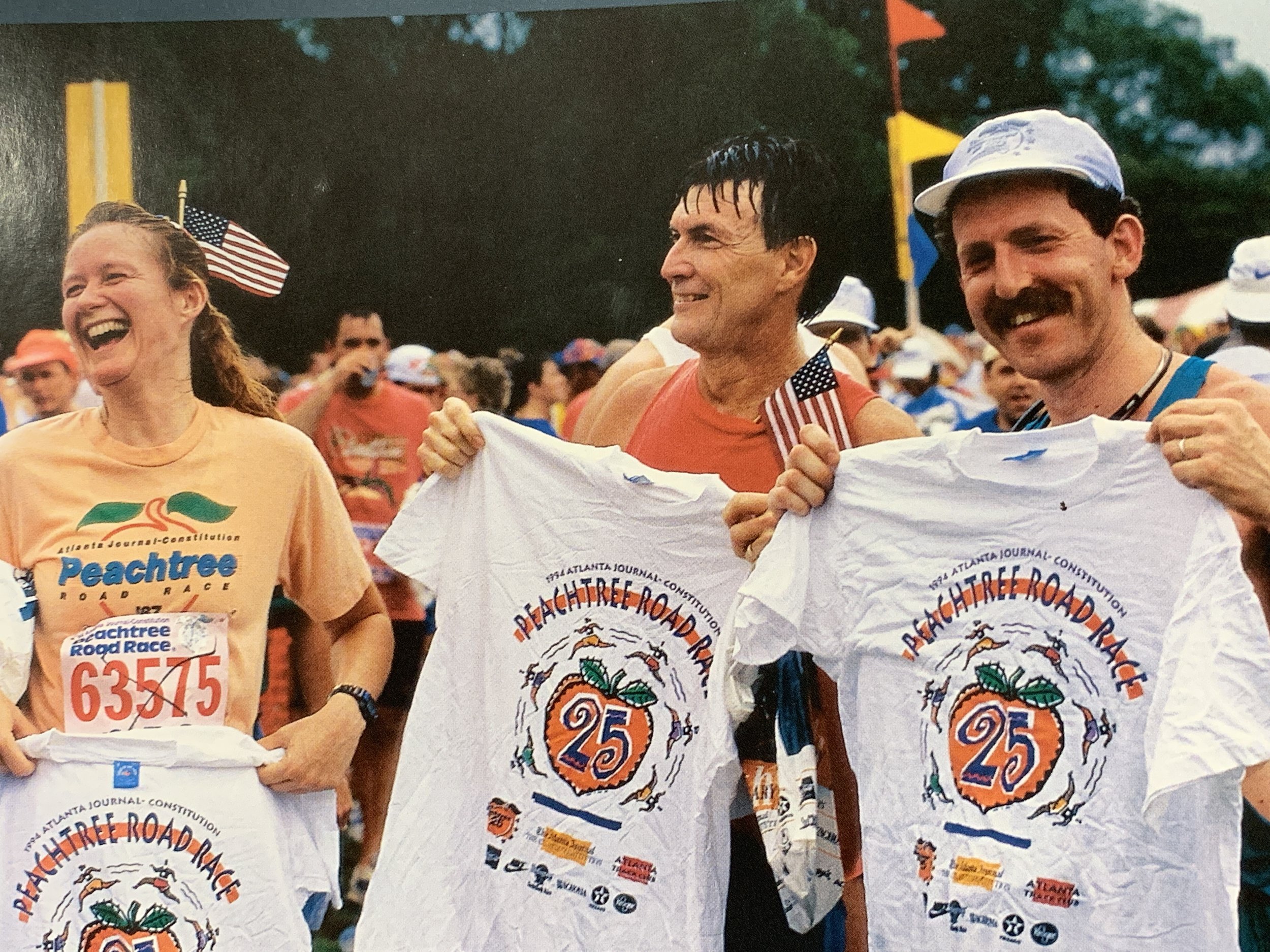

Then came “The Pumpkin.”

1994 marked the 25th Running of the AJC Peachtree Road Race. Atlanta had just been named host city of the 1996 Olympics. The city was celebrating sport and its most well-known endurance event was taking center stage. “This was really the hot ticket,” said Emmons. “It was supposed to be the best T-shirt ever.”

To come up with the design, Emmons again turned to her colleagues at the AJC. Inspired by shirts at the popular Bay to Breakers 12K race in San Francisco, she asked for a “bouncy, California-esque” design that might appeal to a younger audience. While she admits she didn’t love the final product, she never expected the oncoming backlash. The onslaught came quickly.

“I am not sure I knew how bad it would be on race day,” Emmons said. “But there appeared to be a groundswell of profound dismay.”

Angry Peachtree finishers picked up their phones and their pens to share their outrage with the overwhelmed employees of Atlanta Track Club – all three of them. “The phone rang off the hook for days if not weeks,” recalled Emmons. “They were furious at me. People said it ruined their lives.”

Janet Monk, now the Club’s manager of special projects, had just joined the staff. “You didn’t want to answer the phones,” she said. “But you would have to and be gracious about it.” Emmons said she personally received petitions signed by hundreds of people asking her never to do “that” again.

The Club didn’t shy away from sharing the feedback. That September’s issue of Wingfoot Magazine published letters from disappointed runners. “There was one part of my day that dampened my spirits,” wrote Leonard Roy. “That was seeing ‘The Shirt.’ The peach in the center looks more like a pumpkin than a peach.”

As the race director, Emmons had signed off on the design and felt that its failure fell squarely on her shoulders. Following the pumpkin debacle, she waved the white flag. “I said ‘that’s it. I’m not choosing it anymore,’” she recalled.

And thus the AJC Peachtree Road Race T-Shirt Contest was launched.

Emmons attributes the idea to then-AJC Publisher John Melton. The contest was announced on the pages of that very paper in October of 1994, open to anyone 12 and older, with a prize of $1,000. Designs could be hand-drawn or done by computer and could include up to eight colors. By the time submissions closed in February, 751 entries – from the drawings of grade school students to the designs of professional artists – had been mailed to Atlanta Track Club’s offices.

A jury made up of representatives from Atlanta Track Club’s staff, the AJC staff and local artists selected the five finalists. Then, the public voted by calling a special hotline set up just for the contest.

Carl Wattenberg III, then a recent graduate of the Academy of Art in San Francisco, entered the contest at the urging of his mother, a Peachtree runner. Wattenberg, a self-described computer geek who worked as a cashier at Computer City at the time, recalled spending weeks working on two designs. Just days before the deadline, he realized that each artist could submit up to three, so he “made the third design on a whim.”

That design ended up winning the contest and was printed on the shirts of the 50,000 finishers of the 1995 AJC Peachtree Road Race. “It was really amazing to see all these people wearing the design,” said Wattenberg who now designs video games in California. A quarter century later, he still recalls the process behind the art. “You’re thinking about not showing too much gender or race. You want to cover all your bases and the best way to do that is to paint like a child.” Using Adobe Illustrator, he did just that and became part of Peachtree history.

The contest has continued for the past 25 years. There is no formula for creating the winning designs. American flags, footprints, shoes and, of course, peaches are all popular. But cityscapes, street signs and the occasional silhouette of a runner have also appeared in winning art. “Only think of two things – the gun and the tape,” said Sam Mussabani, whose design featuring a runner in full stride won the 1996 AJC Peachtree Road Race T-Shirt Contest. “When you hear one, just run like hell until you break the other.”

The winners have ranged from “computer geeks” like Wattenberg to race participants like Tina Tait, a graphic designer and avid runner who won the contest in 2015. “This year, I just decided it was my year,” Tait told the AJC in 2015. “Peachtree is my favorite race, and I just felt like it was time I submitted one.” The 2018 winner, Michael Martinez, told 11Alive that he was at Mile 5 when he found out his design won, but didn’t actually believe it until he crossed the finish line and got the shirt himself.

For the 50th Running, local celebrities and institutions with deep ties to the event were invited to collaborate with designers on a submission for the final designs. Artwork was submitted by the Atlanta Braves, whose design was done by the team’s creative director; Harry the Hawk, who worked with the Atlanta Hawks art department; Jeff Galloway, the first winner of the Peachtree, who worked with a local illustrator; New York Times best-selling author Emily Giffin, who worked with Tait, the 2015 winner; and Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, who worked with a designer in Atlanta City Hall.

The decision was loved by many, hated by many and talked about by everyone. So were the designs when they were unveiled on March 1.

“In its 50th Running, we wanted to spread the word to as many people as possible about the Peachtree,” said Rich Kenah, Atlanta Track Club’s executive director. “By working with these Atlanta icons, the message of the shirt and the growing movement of health and wellness reaches new communities here in Running City USA.”

Love the designs or hate them, Atlanta Track Club expects to spend nearly $400,000 on shirts for the 60,000 expected finishers.

While tweaks may be made here and there, the tradition of the T-shirt will likely last at least another 50 years. Its importance isn’t lost on the staff. No one on the staff of 30 at Atlanta Track Club will wear the finisher’s shirt. Why? They didn’t run the race. In fact, many learn of the winning design at the same time as the participants.

“It’s something people really care about,” said Emmons. “And you can’t let them down.”