The Year the Peachtree Grew Up

Bill Rodgers won the Boston Marathon four times. Bill Rodgers won the New York City Marathon four times.

Bill Rodgers lost the AJC Peachtree Road Race twice. And he hasn’t forgotten about it.

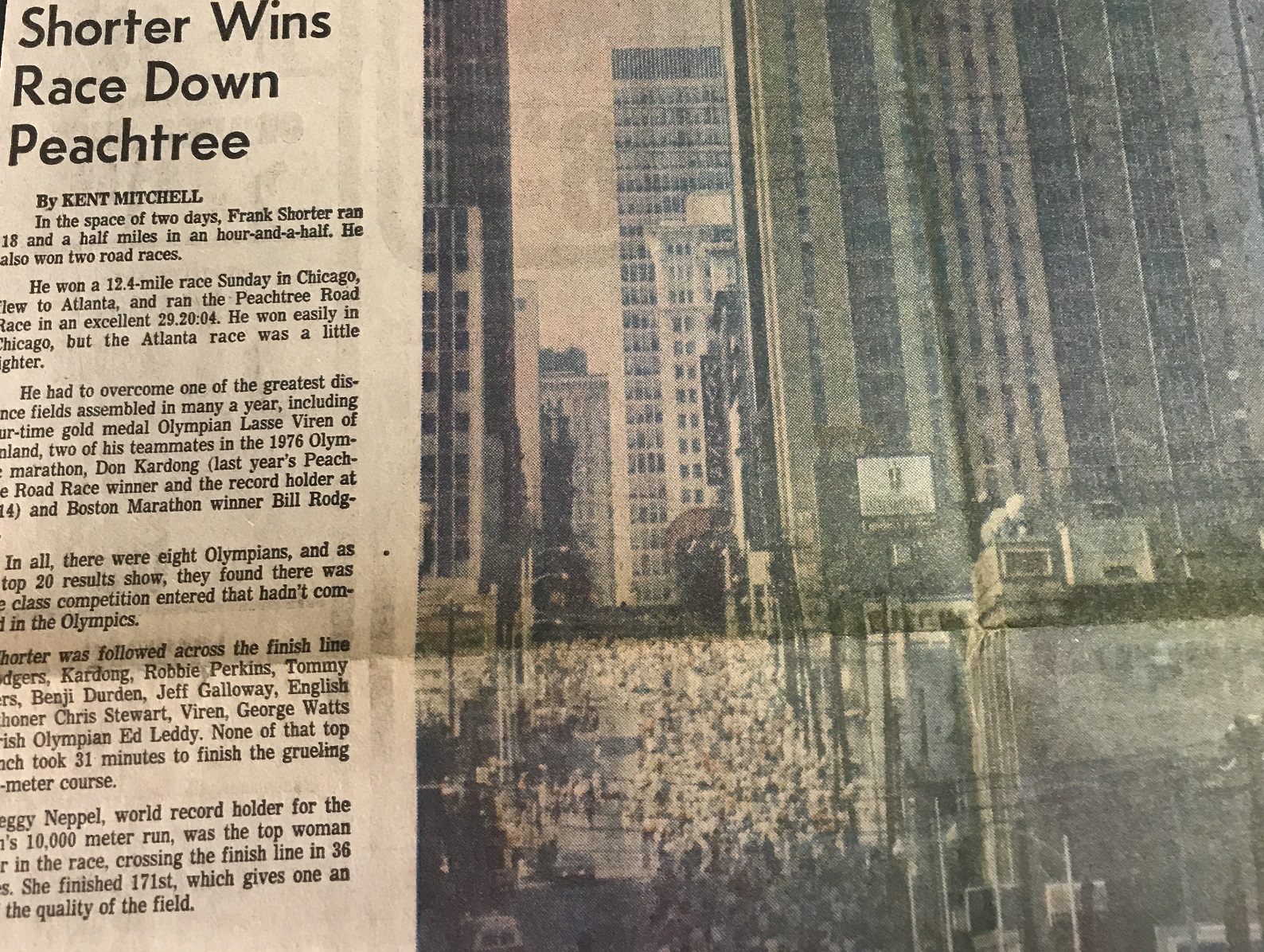

Rodgers reads back the entry from his training log from July 4, 1977: “Placed second in 10,000 meter over hilly course to Shorter. 29:26, 10 seconds slower than I ran last year, but it was much hotter this year. Ran very hard!”

That year, Rodgers was second in the edition of Peachtree that forever changed the race and, to no small extent, played a starring role in the evolution of U.S. road racing.

Bill Rodgers. Frank Shorter. Don Kardong. Lasse Viren. Four of the best distance runners in the world at the time stood on the start line, followed by 6,500 citizen runners. Never before had so many lined up to share the road with such greatness, and the influential athletes who ran say it helped establish the model used by the country’s most iconic road races today.

The competitors in that race unanimously credit one man for bringing them all together: Fellow Olympic runner and Atlanta native Jeff Galloway. Galloway credits the race’s title partner, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Their roles in organizing the race collided at just the right time, setting the stage for history.

The transformation actually began the year before, in 1976. Race founder Tim Singleton had stepped down as race director and moved to Texas, leaving the race in the hands of Galloway and Bill Neace. Neace had heard through the grapevine that a young Cox Media executive named Jim Kennedy was a runner. With Carling beer out as a sponsor, the door was open for the Cox-owned AJC to not only sponsor the young race, but also to use the power of the press to promote it.

At the same time, Galloway – still running competitively but looking for alternative ways to make a living through running – had the idea of bringing world-class runners to Atlanta. “It was my vision to take this wonderful venue of Peachtree Street and blast it out to the running world as a super venue for road racing,” said Galloway. “It was my desire to bring my friends, show off our city and have an event that would make a national impact.”

With just months to spare before the 1976 running, Galloway persuaded two of his friends to travel to Atlanta: Don Kardong, who was training for the upcoming Olympic marathon in Montreal, and Rodgers, Galloway’s old college teammate at Wesleyan who had won the 1975 Boston Marathon. “The beauty of knowing these guys was that I could just call them up and get their commitment,” said Galloway, who not only hosted Rodgers but, the Boston champion recalls, introduced him to grits.

Kardong would win the race in a new event record of 29:14, with Rodgers just two seconds back.

As soon as the race was over, Galloway and Neace got to work on the 1977 running, meeting for lunch daily to strategize. With Rodgers and Kardong, the Peachtree had already gone national. Galloway wanted it to be international. To do that, they needed a foreign headliner. Galloway knew exactly who he wanted: Lasse Viren. The Finnish runner was arguably the best in the world, having won the 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters at both the 1972 and 1976 Olympic Games. In 1976, he even placed fifth in the marathon just 18 hours after the 5,000-meter final.

By chance, Neace knew a professor at Georgia State University who was a prominent member of Atlanta’s Finnish community, and through him they were able to make the invitation. Viren was hesistant, but remembered meeting Galloway at the Olympics in Munich. After months of back and forth, the Finn was in.

“This was huge news,” Galloway said. “In 1976 there weren’t a lot of people in the South who knew who he was. By 1977, they did.”

Like Kardong and Rodgers, Shorter was another of Galloway’s buddies. Credited with igniting the running boom with his 1972 Olympic Marathon gold medal, Shorter was coming off a silver medal performance at the 1976 games.

“I am not sure of the name of the race,” he told a reporter in Chicago in 1977. “But my friend Jeff Galloway called me and asked me to run and that’s why I am going.”

With the big stars on board, other world-class runners wanted in on the action. “I was answering the phone almost every day from some athletes somewhere around the world who wanted to come,” said Galloway.

Ed Leddy, the 1975 Peachtree champion and Irish Olympian was added to the field, as was Olympic marathoner Kenny Moore. Local running star Benji Durden signed up, and Duke University standout Robbie Perkins got into the mix. Great Britain’s Chris Stewart joined in. Even Galloway himself, undertrained due to his business commitments, got a race number.

Galloway understood that a star-studded field was worthless without good marketing. Through the new relationship with Cox, he had access to not just the AJC, but also to the company’s radio and television stations.

“Whenever I would get one of my friends to commit, we would announce it. The excitement started growing,” said Galloway. People would come into his running store, Phidippides, to register for the race, excited to stand on the start line with the likes of Rodgers and Shorter. Along with the elite athlete announcements, the AJC’s editorial and lifestyle staff began publishing articles about the health benefits of running and tips for beginners. Galloway would follow each article with a clinic on the same topic at his store.

The word spread outside the confines of Atlanta. That year, the race was named the Road Runners Club of America’s 10K National Championship. Runner’s World magazine named it one of the Top 10 running events in the United States. And participation exploded. In 1976, 2,350 people registered for the race. In 1977, that number was more than 6,500. (A highly publicized matchup between Shorter and Rodgers at the 1975 Falmouth Road Race helped spur growth there, too, from 850 runners in 1975 to 1,856 the next year, when Shorter would beat him again.)

By June of 1977, Atlanta and the entire running community was buzzing about the Peachtree. “Before the mid-70s, the biggest road races in the world had a couple of hundred runners,” said Kardong. “The Peachtree was right out there and it was a lot of fun.”

Shorter, ironically, may have been the least enthused after being immediately turned off by seeing the Peachtree’s infamously hilly terrain. In 1994, reminiscing about that watershed year, he told journalist Karen Rosen that he left his racing shoes on the top of a car the night before the race, hoping someone would steal them. They didn’t, and Shorter, shoes and all, was standing on the start line that Monday morning.

Even by Atlanta standards, it was hot that morning. The temperature was 80 degrees at the start, still tied for the warmest starting temperature in race history. Runners dropped out by the dozens, 60 of them needing to be taken to the hospital. Kennedy, the newspaper man, completed the race in 32:00 and recalls the postrace area looking like a scene out of “Apocalypse Now” with disoriented runners falling and helicopters flying overhead. The race’s headliner, Viren, would be among those falling victim to the heat, initially going with the leaders but fading in the final mile to finish a disappointing ninth.

His American counterparts, however, seemed unfazed. From the gun it was a three-man race among Shorter, Rodgers and Kardong, the defending champion.

“I don’t think I knew this at the time, but Frank runs every road race exactly the same,” said Kardong. “He stays back the first mile and then he moves to the front.” That’s exactly what happened. Shorter, who had won a 20K road race in Chicago the day before, surged to the front at Mile 2. A back-and-forth between him and Rodgers ensued with the career-long rivals swapping the lead over the next four miles. With a quarter mile to go, Shorter found another gear and sprinted to the finish, besting Rodgers by seven seconds with a time of 29:17. He told reporters it was the best he’d ever run before breakfast. Kardong was third. Galloway placed seventh.

A clipping from the 1977 Atlanta Journal-Constitution

With all the focus on the men’s race, 10,000-meter world record-holder Peg Neppel of Iowa remained largely under the radar in winning the women’s race in 36:00. In 1977, women’s distance running was still not widely accepted on the world stage, with no race longer than 1,500 meters added to any major global competitions until the 3,000 meters was added to the World Championships in 1980. (In 1978, 19-year-old track star Mary Decker would race the Peachtree because of Galloway – garnering both the win and significant media attention.)

The Shorter-Rodgers rivalry would continue less than six weeks later, with Rodgers beating Shorter at the Falmouth Road Race in mid-August. In the fall, Rodgers would win his second consecutive New York City Marathon.

As for the third-place finisher, Kardong took the Peachtree concept back home, where he organized the first Lilac Bloomsday Run in May of 1977.

“I just thought it was a great idea and I said ‘we can do this in Spokane,’” he recalled. “I think Jeff was ahead of his time in terms of conceptualizing the whole idea of what a road race can be in bringing in the Olympic athletes and encouraging everyday runners, too.” Today, with Kardong as the race director, Bloomsday is one of the largest road races in the United States, with 40,000 annual participants.

Neither Shorter, Rodgers nor Viren ever came back to the Peachtree. Kardong ran once more, in 1978. But their legacy lives on, paving the way for the national, world and Olympic champions who have broken Peachtree’s tape since their groundbreaking run more than four decades ago.